I first became aware of the concept of elopement when reading the book Traveling Different – Vacation Strategies for Parents of the Anxious, the Inflexible, and the Neurodiverse, by Dawn M. Barclay (see Traveling Different book review here). I’ll admit I had to look it up. And when I did, I realized that one of our neurodiverse sons had eloped earlier in life but not in quite a while.

I naively thought we were safe from any more of that, but soon came to realize it is a very real and potentially dangerous problem for many children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and our family was much less safe from it than I thought.

Elopement – What it is and its disproportionate impact on neurodiverse families

Elopement is when an individual leaves a safe environment without notifying anyone. Sometimes it’s referred to as wandering, running away, or bolting.

According to an analysis of data of more than 1,300 families enrolled in the online research database and autism registry Interactive Autism Network (IAN), nearly half (49 percent) of children with ASD have attempted to elope after 4 years of age. According to the respondent population, for siblings without ASD the number comes way down, to 13 percent.

Elopement of any child can be an incredibly scary experience for both the child and the family, but if it happens when you are away from home, the reasons for concern can escalate.

Our elopement story

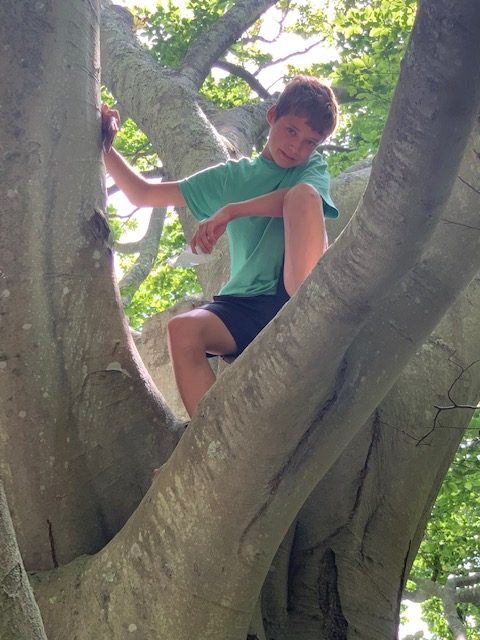

Shortly after reading about elopement in Traveling Different, it happened to us. Our oldest son Jeffrey, nearly 15 years old, used to run away from us often when he was much younger – between two and five years of age. He’d usually do it with a smile on his face, like he thought it was a game, and never picked up on the fact that we were panicked, begging him to stop, shouting his name, and stressed out when we finally were able to catch up to him or find him.

Often, he would elope as we were moving from our house to the car. So, we had a fence installed and parked inside of it. Within a day, he figured out how to push the fence open and the elopement continued.

One elopement I vividly remember happened at the White House Easter Egg Hunt. It was a mob scene – tens of thousands of screaming kids and parents following behind. We’d gotten much of the way through the event, and two-and-a-half-year-old Jeffrey seemed to be having a blast – smiling, twirling, running around to activities, and scattered eggs. Then suddenly, he kicked into high gear, wedged himself into a crowd, and disappeared.

We searched nearby crowds of kids in vain and found the closest security officer who relayed the situation to a network of staff whom we armed with details of his physical traits. They moved into action and thanks to their help, Jeffrey was tracked down within a few minutes. We felt deflated from the experience and I’m sure Jeffrey had trouble understanding why, when we were at the greatest easter hunt in the world, his parents were unhappy.

I always thought when he eloped, the game was at the heart of it, but after recently researching elopement, I now know that for neurodiverse kids, there can be a lot more to it.

Over time, the running stopped, and we were relieved that it was behind us. Fast-forward to our August 2022 family vacation. We had mostly ups during the trip – great weather and food, fun excursions, time with family – but a few downs toward the end. All in all, though, as we headed into the last day, my husband and I were proclaiming it a success.

On the morning we were getting ready to drive back home, we had divided up the remaining cleaning and packing duties, and most family members were rolling up their sleeves, but Jeffrey was less enthusiastic. He’d indicated the night before that he didn’t have much interest in helping with this necessary effort to get out the door, and we tried to reason with him, lay out the plan for him and give him his own discreet tasks, and finally, when these things didn’t work, we expressed our frustration. He vowed to do better.

But the morning of our departure brought more pushback. After a little while, he decided he had helped enough, and started playing board games by himself as we vacuumed and cleaned up around him. His lack of wiliness to help made everyone unhappy – from his youngest sibling to his oldest parent.

He finally decided he’d just go outside to hang out with the family dog, who wasn’t going to pile on. When we started moving luggage out to the car, he was hiding from us, but we could see his shoes underneath the outdoor shower. Then, during one trip from the house to the car, I noticed I couldn’t see his shoes under the shower anymore. We looped around the inside and outside of the house but there was no sign of him. And calling him was not an option after we’d confiscated his phone out of frustration.

We split up and called other family members who were staying nearby to help us search. We started by going to his usual haunts – the neighborhood market, playground, then headed down toward the water. At that point, with the water spreading out before me, a feeling of dread crept in. Our other neurodiverse son Jack decided to run the length of the beach to look for him, to no avail.

We got back in the car and as we weaved through the neighborhood streets again, the tears and prayers began to flow faster, and I readied myself to call the police. Then the text came through from my husband that he had found him at the swings, where we had looked 20 minutes prior. Brother Jack – his best friend in the world – walked over to him, talked with him for a few minutes, somehow said whatever Jeffrey needed to hear, and they both walked to the car. We told him we loved him, explained why we’d been so scared that he’d run away, and put on a book on tape to get back to an emotionally normal place. Crisis averted, but it felt like we had perhaps entered a new, possibly slightly darker phase of Jeffrey’s teenage years.

I understand we are lucky with how things turned out – my online research on elopement leads to devastating stories. But that search also leads to helpful information and guidance.

Why elopement happens more among kids with ASD

The reasons elopement happens much more frequently among kids with ASD vary and include the following, pulled from this helpful article – https://www.appliedbehavioranalysisedu.org/:

- “Children with ASD may not have the same level of awareness that a neurotypical child might have, the kind of awareness that makes a child intuitively or knowingly try to avoid dangerous situations.”

- To leave a situation that feels overwhelming or unhappy for a calmer place. This can include arguing with or around them, too much noise or other things.

- “The child loves the feeling of running”.

- They are “attracted to something that was more appealing than what they were currently involved in” – e.g., if an environment evokes stress or anxiety, they may seek to escape to a place they view as less stressful.

- To “pursue something they want,” or get to a place they enjoy.

What to do to plan for or minimize elopement when traveling with your neurodiverse child:

First know you’re not alone. Elopement is a significant issue for the families of neurodiverse children, and a major source of stress for parents. According to the above-mentioned IAN survey:

“Wandering was identified as one of the greatest causes of stress in families with children on the spectrum. A little more than fifty percent of parents said elopement was the hardest behavior to negotiate. Most of those parents also reported losing sleep over their concerns, worrying whether or not their child would leave home.”

And according to the same study, it’s not a sign of bad parenting. “Parents that experience the issue are often those who closely monitor their child, install locks and alarms on every door and window in the house, and secure gates, fences, and pool enclosures in the yard. Even with all the safety measures in place, your child may still be able to slip away.”

According to the recently reviewed book Traveling Different, some travel venues take steps to help families anticipate and help manage child elopement, such as providing GPS tracking bracelets and enclosed beach areas. Inquire with travel and lodging providers and destinations about their elopement support services before you go on a trip.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) also provides lists of strategies to plan for and try to prevent elopement if possible, and to manage the situation if a child does run or wander off. These lists include:

- Noticing signs that a child may wander off (e.g., looking toward the door)

- Providing a safe location

- Informing neighbors and school workers about your child’s elopement tendency

- Putting in place an emergency plan

- Keeping the child’s information up to date (e.g., picture, description)

- Keeping an ID bracelet or information card on the child

- Teaching your child safety skills, such as swimming, crossing the street, responding to safety commands, and knowing their name and phone number

The CDC page on elopement also addresses the role of first responders and healthcare and other professionals in helping to address the issue when it occurs.

We also have had conversations with Jeffrey about the dangers of elopement and will have many more, before, during, and after travel. And I don’t think I’ll ever take his phone – with its GPS function – away ever again.

What are your strategies for trying to prevent and manage eloping during or outside of travel? Your input is important – thanks for anything you are willing to share!